The gathering of online-user data is among the most exciting and controversial business issues of our time. It often brings up concerns about privacy, but it also presents extraordinary opportunities for personalized, one-to-one advertising. This article is the first in a series exploring the importance of personal data across different industries. It represents a joint effort of The Boston Consulting Group, Goldman Sachs, and BlueKai.

The basic appeal is straightforward: the more a company knows about someone, the easier it should be to target relevant ads to that person. All the stakeholders in the digital-advertising ecosystem—from Google to ad networks to Expedia—are collecting as much information as possible about what their users are doing online.

Over the past five years, we have seen the development of a robust secondary market allowing the buying and selling of user profiles. If someone goes to a travel site to book a room in a Tokyo hotel, for instance, that site can then sell the user’s profile to an ad network via a user data exchange or an aggregator. The next time the user visits a website served by that network, an ad for the Tokyo Hilton might appear.

There are several underlying supply, that is, advertiser, trends that have driven interest in building these profiles:

- A Shift in Campaign Strategies. Advertisers are increasingly moving away from campaigns based on cost-per-thousand data (the cost of reaching 1,000 page views) and toward cost-per-click or cost-per-action strategies, in which advertisers pay only when a qualifying action, such as a purchase or registration, takes place. Ad networks and agencies leverage user data to more effectively target ads in hopes of improving click-through rates, that is, how often a user clicks on an advertisement.

- Growth of Rich-Media Advertising. Video ads and other types of rich-media advertising—which are more interactive and technically complex than text ads—have grown in popularity. Their high cost makes precise targeting crucial.

- The Shift to Ad Exchanges. The purchase of advertising inventory is shifting from networks to real-time bidding on ad exchanges. Advertisers are increasingly incorporating user data to target the ads traded on these exchanges. BCG estimates that the share of online display purchased on exchanges will increase from approximately 15 percent today to 35 to 40 percent by 2015, further accelerating the growth of user data.

Demand-side, that is, publisher, trends are also driving user data growth:

- Advances in Tracking and Analytical Technology. It is easier than ever to track Web users with a variety of techniques such as cookies and Web beacons or tags—methods for revealing who is reading a Web page or an e-mail, when, and on what computer. Advances in analytical techniques have also increased the value of the data collected.

- Financial Pressures on Publishers. Many of these publishers are under pressure from their investors to increase the top line. The sale of user data is an easy way to quickly monetize assets, particularly for subscale content companies that cannot take full advantage of the data themselves.

- Growth of Data Intermediaries. Over the past five years, an ecosystem has emerged to help connect publishers with advertisers, simplifying the process of buying, selling, analyzing, and managing user data from multiple sources.

At the same time, there are several trends that could hamper the growth of this market:

- The effect of spending shifts to Facebook and other “closed” publishers, which have their own rich sets of proprietary data

- Concerns about accuracy, such as when the same cookie is identified as coming from a female user by one provider and a male user by another—a common occurrence when computers are shared

- The proliferation of low-cost remnant inventory, that is, unsold advertising space or time available to media companies for last-minute purchase

- A reluctance to share personally identifiable information because of the threat of regulation and the risk of public backlash

Despite these concerns, we believe that demand for user data will continue to play an important role in the online-advertising ecosystem.

We classify user data first on the basis of how the data are obtained. There are three broad classifications of obtainment: opt-in, or volunteered, data; observed data (first and third party); and inferred data.

Opt-in data, the information users voluntarily provide to publishers when they sign up for services, is the data type of which users are most aware. Sometimes this information is simply an e-mail address, but it might also include an array of demographic information.

First-party observed data are gathered as users surf the Web. Third-party observed data come from the same sources, but companies purchase this information from other websites that have done the collecting.

Inferred data are assumptions that third-party ad networks and agencies make on the basis of observed data combined with opt-in data. For example, if a user is frequently logging on to a college textbook exchange and the website for Cosmopolitan, it is reasonable to assume that the person is a college-age female student. Such inferences are notoriously unreliable, however, especially because the data often come from shared computers.

Opt-in and first-party observed data are the most critical of these data types. They are by far the most reliable, but more important, they can serve as a Rosetta stone when mapped to other, less reliable third-party data to create a more accurate picture of users.

The second way we classify data is according to the nature of the information itself. We break this down into five categories:

- Demographic Data. This includes such information as age, gender, and income and is often at the core of companies’ consumer segmentations. Demographic data can be either volunteered or inferred.

- Behavioral or Contextual Data. These include a user’s interests and attitudes and can be either volunteered or observed based on the type of content consumed or the cookies that track where a computer has gone online. Linking behavioral data to actual purchase intention is difficult; ad networks often need to piece together multiple fragments of information to have a meaningful impact on advertising effectiveness.

- Purchase Intention Data. This information more directly measures a person’s plans to make a specific purchase. It can be volunteered (such as on a lead generation site, where users fill out a contact form, for instance, to learn more about a product); it can be observed, based on actual searches; or it can be inferred, based on past purchases. “Retargeters”—companies that track the products a user looks at but does not buy, such as a pair of shoes on Zappos—have had some success with this type of information by presenting the user with a display ad for the same shoes hours or even days later.

- Social Data. These describe the relationships a person has with other people. From a marketing perspective, social data assume that people who are connected on the Internet have similar attributes or purchase intentions. Such information can be volunteered either through sites such as Facebook or through such interactions as sending someone a newspaper article.

- User Location Data. Marketers are able to identify location using a variety of approaches. This information has historically been gathered based either on the user’s IP address or the sites a user visits. (Someone viewing The Sacramento Bee online is assumed to live near Sacramento, for example.) Interpreting IP address location has become more accurate since the old dial-up days, though it is still difficult. Mobile Internet promises not only to improve accuracy but also to provide user location precisely enough that companies can know when users are shopping and send them coupons that they can use right away.

No single data type can promise perfect targeting. Most marketers make use of several sources to be effective, improving click-through rates by anywhere from 2 to 8 times, depending on the quality of the data. The challenge is that these click-through rates start at a low base.

The exchange and sale of user data is not a new phenomenon. The term “database marketing” was first coined in 1988. What is new is the depth of information available and the automated fashion in which it can now be bought and sold. The market for user data is still young, yet it has already carved out a meaningful position.

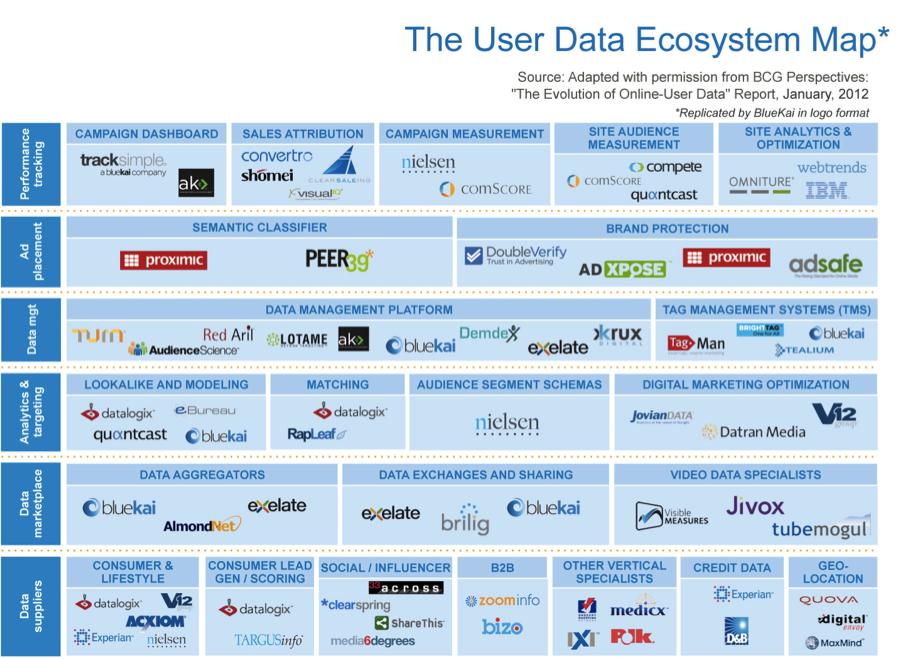

We have mapped the data ecosystem based on the steps by which data are obtained and used. It includes six broad categories of companies: data suppliers, the data marketplace, analytics and targeting, data management, ad placement, and performance tracking. (See the exhibit below, original file from: Bluekai)

This marketplace is far from static. We expect to see some degree of consolidation over the course of the coming years, as companies expand their offerings into adjacent spaces. At the same time, we anticipate ongoing expansion resulting from existing organizations creating new features; from start-ups; and even from new entrants such as IBM and media-communications-services company WPP, which are also investing in the space.

The next three years will likely see gradual changes in how user data are collected and used. We believe that five major related opportunities are emerging.

Promotions Targeting. In 2010, Groupon proved it could drive traffic—and reach $1 billion in gross revenue faster than anyone had before—by sending relatively untargeted offers to consumers. It remains to be seen whether this type of strategy can maintain such rapid growth.

Mobile Advertising. Mobile is already creating entirely new genres of advertising. Since mobile devices are typically mapped to individuals, this category promises real-time promotions and more effective targeting. To date, however, the promise of mobile targeting has not come to fruition because of several technical barriers—not the least of which is the lack of universal cookies on mobile devices. Once these issues are addressed, the opportunities will be huge.

Video Targeting. The rapid growth of online video is creating opportunities to dramatically improve targeting. Some video-advertising networks are already implementing user data, but these experiments have barely scraped the surface of what is possible. One of the most interesting opportunities may stem from Time Warner Cable’s experiments with allowing users to download video content from the cable operator as long as they are in their own home. By combining third-party household data (via the home IP address) with individual usage information, advertisers can reshape the direct-mail business to work within the realm of digital advertising.

Cross-Media Targeting. Marketers everywhere are struggling to find ways to target users across all their media, both traditional and digital.

Spending-Based Targeting. Credit companies already successfully target users based on levels of spending. New technologies, including the tracking of rewards- and loyalty-card activity, mobile payments, and digital receipts, will generate more detailed information and, thus, more precise targeting.

The evolution of personal data will be critical to participants in the ecosystem, from advertisers to publishers and everyone in between. Those who move today will create meaningful and sustainable advantages in the marketplace. The following are the key imperatives for every stakeholder in the personal-data ecosystem.

Advertisers. It will be crucial for advertisers to create channels that enable the direct collection of opt-in and first-party observed data. They will also have to reexamine consumer segmentation in order to map together online first-party data and actively leverage this information to better understand third-party data. Advertisers must increasingly build their analytic capabilities, either internally or via structured partnerships with third parties, and experiment with various types of user data to understand what “moves the needle” from a marketing perspective.

Publishers. A primary role of publishers will be to understand the different types of data that can be collected across all platforms. They must decide whether to sell data to third parties for a new revenue stream, keep information exclusive and thus charge advertisers more, or both. It will continue to be important to gauge how sharing information might affect relationships with users and to identify how to improve the quality of targeting by leveraging third-party data.

Intermediaries (Data Networks and Exchanges). These groups will have to ensure that data policies are well aligned with the evolving regulatory environment with respect to personally identifiable information and invest in creating analytic capabilities—to better serve both advertisers and publishers. They must also partner with mobile carriers, device manufacturers, and other mobile-services providers to crack the mobile problem.

The speed of change in the personal-data ecosystem has outstripped many of the existing normative, legal, and trust frameworks among business, government, and individuals, which could undermine much of the potential opportunity. In the next article in this series, we will examine this problem and propose a framework for addressing it through a series of multiparty structured dialogues that balance specific industry, geographic, and cultural issues with a common set of overarching principles.

- Ed Busby

- Ed is a former partner in The Boston Consulting Group’s media practice and is currently chief commerce officer of Isis, a mobile-payments joint venture of AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile.

- Tawfik Hammoud

- Partner & Managing Director

- Toronto

- John Rose

- Senior Partner & Managing Director

- New York

- Ravi Prashad

- Project Leader

- Toronto

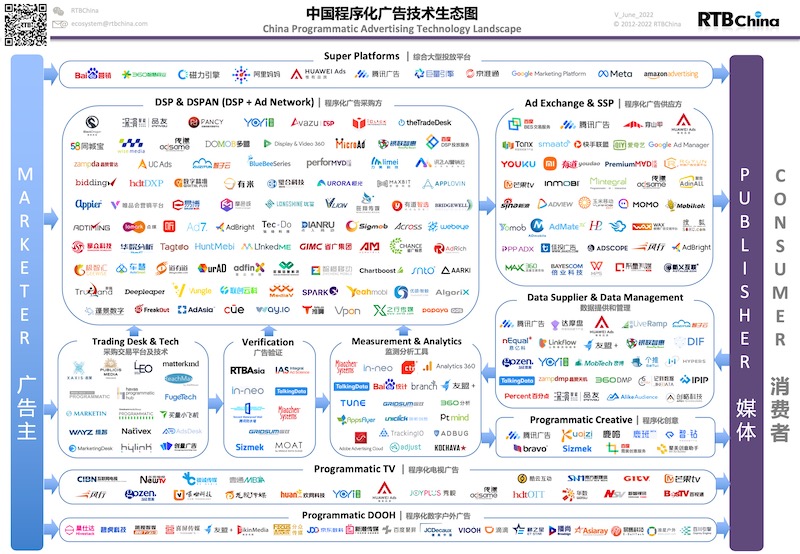

RTBChina

RTBChina